Very little is known about Ciconia‘s early life. He was born in around 1370, probably one of the many illegitimate children of Johannes Ciconia of Liège (a priest) and a woman of high birth. According to Vatican records Ciconia was granted a papal dispensation for his defectus natalicium which allowed him to hold ecclesiastical posts and gave him leave never to admit to his illegitimacy again.

Very little is known about Ciconia‘s early life. He was born in around 1370, probably one of the many illegitimate children of Johannes Ciconia of Liège (a priest) and a woman of high birth. According to Vatican records Ciconia was granted a papal dispensation for his defectus natalicium which allowed him to hold ecclesiastical posts and gave him leave never to admit to his illegitimacy again.

He was employed by Papal Legate of cardinal Philippe d’Alençon and was based in Rome by 1391. He seems to have been associated with the court of of Giangaleazzo Visconti from the early 1490s until the end of the century.

In mid 1401 Ciconia was appointed to a benefice in the church of S. Biagio di Roncalea and granted a chaplaincy in the cathedral. By 1403 he had become cantor et custos at Padua Cathedral, holding the position until his death in 1412.

Ciconia’s musical style is difficult to pin down; his secular works cover a wide variety of genres and he set texts in several languages. He mastered a kaleidoscopic assortment of idioms, equally at home with the French Ars Nova, the Northern Italian Trecento, and the Ars Subtilior.

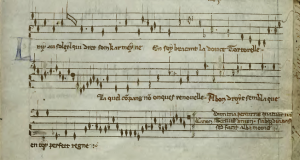

Le ray au soleyl is a striking, almost minimalist work; a shimmer of overlapping sounds and a fitting conclusion to the frenetic experimentation that dominated musical expression in the late fourteenth century.

The text of Le ray au soleyl contains references to one of the emblems of Giangaleazzo Visconti—a dove holding a ribbon bearing the text A bon droyt, designed by Petrarch for the occaission of Visconti’s second marriage in 1380 to his cousin, Caterina. The canon has been dated to the 1390s on the grounds of this association.

Le ray au soleyl is a prolation canon—a canon based on ratios of speed rather than time delays—in this case 4:3:1